HQIP response to “Institutional Use of National Clinical Audit by healthcare providers.”

Published: 26 May 2020

The recent paper – Institutional Use of National Clinical Audit by healthcare providers McVey L, Alvardo N, Ken J at al. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;1-8. DOI: 10.1111/jep.13403 – from colleagues looking into institutional use of National Clinical Audit, concluded that there is an imbalance between the benefits to institutions and the required resources for participating in the national audit programme. This study is based on interviews with 16 colleagues, is semi-structured and comes across as relying more on anecdote. There were additional interviews with 32 clinicians, although it is not clear how the findings from these colleagues reflect on the reported imbalance between the national programme and the Boards of Trusts.

The criticisms in this report are not new and HQIP has been working with audit providers, clinicians, commissioners of care, regulators and patients, to move the programme from one designed for assurance to a much more responsive programme providing assurance but also working as a vibrant improvement tool.

The findings from these 16 interviews gave a heterogenous set of opinions:

- Detailed information and outcomes do not feature in key Trust metrics unless there are reputation issues concerning the Trust. Accordingly, audit staff are tasked to review the reports in case there was any reputational issues and not as improvement tools. Trusts viewed the quality improvement as being aimed at clinicians.

- Trust committees reviewed reports by exception with a risk emphasis, again missing the opportunity for improvement.

- The results were generally slow and too retrospective. They needed to move to more real time, such as seen in the hip fracture audit.

- The format of annual reports is too heterogenous, of variable length, format and with variable recommendations.

- The national programme is unrealistic with inappropriate metrics, and too many metrics. They are added to and are too resource intensive in Trusts.

- The programme needs to concentrate on institutional priorities, particularly on the requirements of the regulators. There was a complaint regarding the perceived ability of anyone to set up a so-called national audit that Trusts have to respond to.

We have been addressing virtually all of these challenges over the past five years. Indeed, Dominique Allwood worked with us when she produced our cited report. Since this time we have made strident efforts with audit providers to address many of these issues with the caveat that we are responsible only for the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP) commissioned audits.

National clinical audit benchmarking

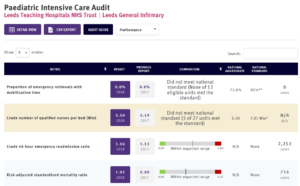

The HQIP-instigated initiatives have been to help bring the results and recommendations from the national programme most easily to those who can implement them, including clinicians, audit and quality improvement departments and Trust Boards. These have included the increasing use of infographics and displaying results in a single page pdf in the National Clinical Audit Benchmarking (NCAB) initiative. Both audits which form the basis of this review, PICANet and MINAP, feature in the NCAB programme (illustrations of relevant NCAB slides in Figure 1 and 2 below).

Feedback on NCAB slides, which are produced in conjunction with the analytics team in CQC, is excellent and NCAB addresses several of the themes highlighted in the article. They have been produced to reduce the work audit teams have to do in reporting national results to Boards and are a quick resumé of annual results for all concerned. They deal with the concern that the programme address provider Trusts’ priorities as they relate to regulators, as they are produced with CQC and have CQC’s comments incorporated on each slide.

“We cannot afford to lose the good while we wait for the new.”

We have been working with audit providers on the dual themes of real time versus very retrospective results. To produce reliable results which might show poor performance there needs to be agreement by all that the techniques and collections are beyond reproach. This requires considerable focus and does give a very assured result. Real time results will never be assured in the same way and are yet the direction we need the programme to move to. We need to be able to blend the processes. Systems such as electronic patient records collected as routine data will possibly answer this, but we still need the data to be assured. Definitely there are ways of using digital technology to help but this may be a slow journey and we cannot afford to lose the good while we wait for the new.

As specified in the article, the Hip Fracture registry has moved successfully to give near to real time data with an assured process and we see this as a model we wish other audit providers to adopt. The National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes research (NICOR), the host organisation for MINAP, and PICANet have both responded to the Coronavirus crisis. PICANet is producing, currently, real time data to track current events. This may well be the model that we can encourage after the crisis has settled.

We have been working with the national body supporting local audit staff, National Quality Improvement (including Clinical Audit) Network (NQICAN), so that the voice of staff who articulated their frustrations in this article are heard by us and others. Their chair has a seat on various of our groups where these themes are expounded. We work closely with NQICAN to address their concerns.

Quality improvement

One other theme concerns the fairly narrow version of quality improvement (QI) developed in the article. We believe that QI is everybody’s job and were surprised not to see it being developed along the lines of the Institute for Health Improvement’s model of small-scale changes leading to sustainable improvement. We have never come across a healthcare organisation which has raised a financial objection to an initiative that has come through this system and has demonstrated improvement. We accept that the national programme as a whole could produce a set of recommendation which would be daunting for an organisation to implement but this is the role of clinician leaders who can champion the relevant initiatives at local level proving that such change is leading to improvement.

Danny Keenan

Medical Director

Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership

Figure 1

Figure 2